HOUSTON — WARNING: Some of the video shown above and below may be difficult to watch, as it contains audio of a 911 call from a domestic violence survivor. Viewer discretion is advised.

Domestic violence victims often suffer alone, hiding the ugly, the painful, from family, friends, police and even themselves.

We first met “Samantha” in January of 2020. Six years had passed since her divorce, but some fear still lingers.

“Samantha” isn’t her real name. It’s safer this way for many reasons, including, she says, because he’d threatened her with a loaded shotgun in the past.

“There were red flags from the beginning that I didn’t notice, because I just was ignorant, and I just didn’t know,” Samantha told us.

Samantha was married to her husband for 19 years.

“An abuser will use whatever tactic they need to keep power and control over you,” she said. “Sometimes they need physical abuse, sometimes threats or fear or embarrassment."

“As a Christian woman, I didn't believe in divorce,” Samantha added. “I mean, you just make it work, because you don't want to put your kids through that."

“Why did I stay? I guess, I guess I thought I had to, and once I realized I didn't have to, it was a game changer,” Samantha said.

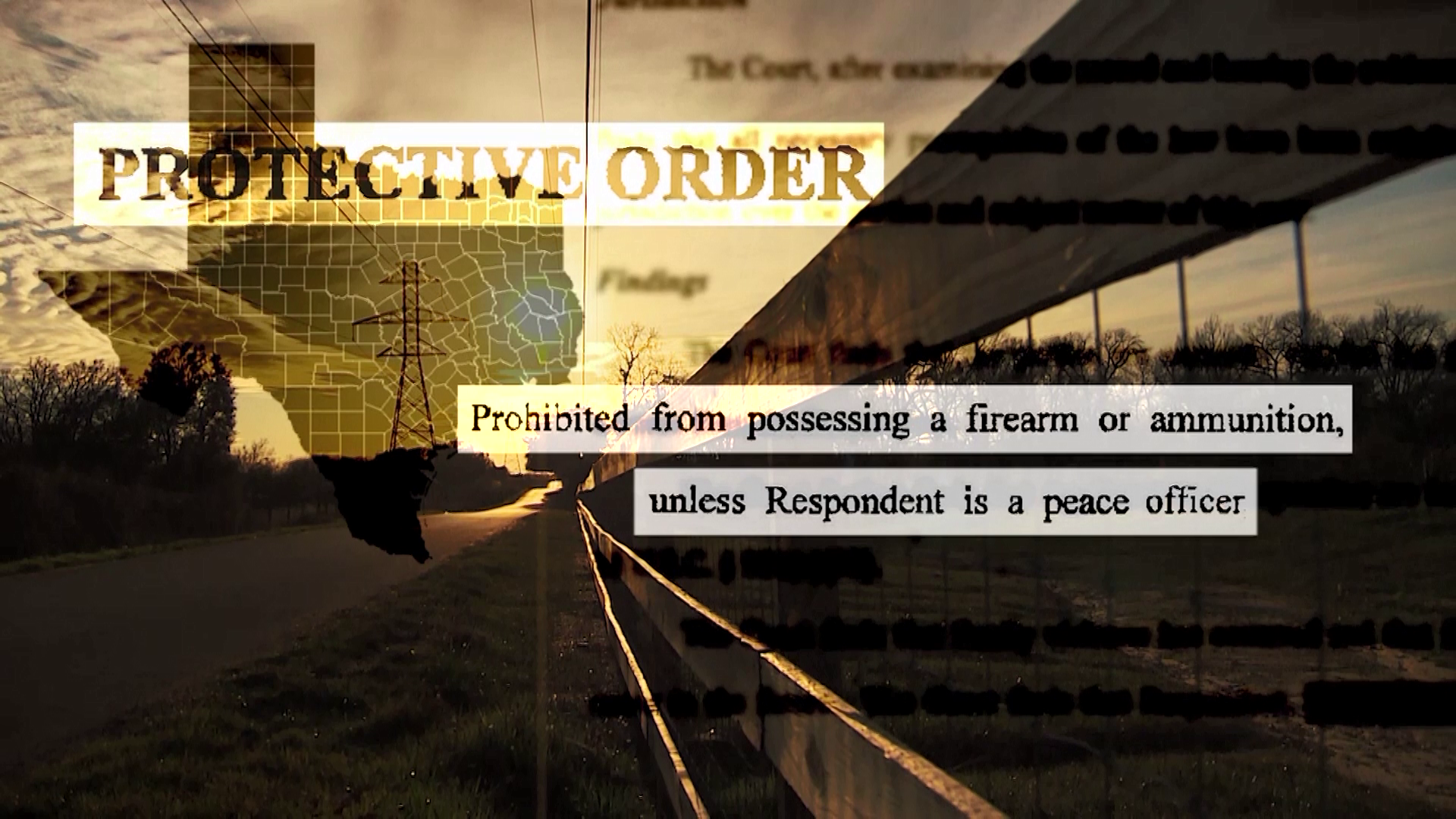

It took months to leave, file for divorce and get a protective order against her husband, which prohibited him from possessing or carrying a firearm or ammunition.

“He was in possession of guns and ammunition the whole time during the protective order, so it's just a piece of paper. It didn't matter,” Samantha said.

Editor's note: The video for the first part of this story can be viewed in the player above. To see the second part of this story, watch the video below or click here.

In Texas, if a protective order is issued against you, you can’t possess a firearm or ammunition. That’s been spelled out on protective orders for more than 20 years -- except in cases where a respondent is a peace officer with a full-time state agency job.

As of Sept. 1, 2020, trial courts are also required to inform people regarding prohibitions outlined in their protective order.

“(The court must) orally admonish the person, in a manner the person can understand, that the person is ineligible to possess a firearm or ammunition; and provide the person with a written admonishment informing that person of the person's ineligibility to possess a firearm or ammunition,” a chapter in the Texas Administrative Code states.

But based on multiple conversations with lawmakers, attorneys, judges, law enforcement and advocates across the state, we found that most of the 254 Texas counties don’t have a formal process for the surrender, storage and return of those guns.

“I don't think across the state it is being enforced,” said Jan Langbein, CEO of Genesis Women's Shelter and Support in Dallas. “I think it is hit and miss. And you know what? If it's your sister or your mom or your daughter, do you want hit, or do you want miss?”

Langbein has been working in the victim advocacy field for almost 30 years.

“It's not that I'm against gun ownership. I'm against gun ownership in the wrong hands,” Langbein said. “We know that the very presence of firearms in the home ratchets up lethality 500 percent. Those are the guns, the guns that start in the home and spill out into a Walmart in El Paso or a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, or a school in Parkland, Florida. Those are the guns that I'm against.

Texas Council on Family Violence works on abuse issues across the state.

In 2019, TCFV says 63 percent of women and 68 percent of men killed by domestic partners were shot.

“There are a lot of things that that aren't being done,” Langbein said. “Rarely do we have hard conversations about guns. I don't know that we need stronger laws, but I know that we are now needing protocols and laws to help us enforce the laws that are on the books.”

Even though TCFV is one of the largest domestic violence coalitions in the country, it does not have a complete list of Texas counties that have gun surrender protocols. To get a full picture of what is going on in the state and what counties, judges, prosecutors and law enforcement are doing or not doing, we reached out to multiple statewide advocacy groups working in the domestic violence arena, prosecutors and sheriff’s offices in the state’s 15 largest counties and judges across the state. Getting a complete picture in a huge state, with many people not returning our calls and emails, proved to be difficult.

From the agencies and officials who called or emailed back, we found eight counties out of 254 in Texas that have gun surrender protocols for domestic violence protective order respondents to dispossess themselves of guns or ammunition.

“Even the counties who have protocols, they are limited in what they are doing in terms of enforcing the gun possession prohibition,” said Alexandra Cantrell, now former Public Policy Manager for TCFV. “The gun possession prohibition enforcement is one of our (TCFV’s) number one priorities second session running.”

The eight counties that have gun surrender protocols in place include Harris, Dallas, El Paso, Travis, Fort Bend, Williamson, Galveston and Hidalgo. All have a partnership with their sheriff’s offices to accept, store and return the guns.

In general, the procedures are similar. A protective order is issued, a judge orders gun surrender.

It’s up to the person who’s ordered the surrender to admit how many guns and rounds of ammo they own. A victim can testify to the number of weapons in the home. Prosecutors have told us that sometimes they use social media to get this information. The guns are stored by the sheriff’s offices. Some counties allow the sale of guns or transfer to a third party. The guns are returned upon the expiration of the protective order.

A judge in one county that has a process of surrender told KHOU 11 that while the county may have a program in place to follow up on the gun possession prohibition outlined in protective orders, not every judge orders the surrender.

“There are no set protocols in this area with any of the law enforcement agencies where there's just an automatic standard that, OK, a protective order has been done either by a justice of the peace or by a county court of law or district judge, and the guns are automatically ordered to be turned over,” said Judge Alfonso Charles, who oversees the 124th District Court in Gregg County and Longview, Texas. He’s also the regional presiding judge of the 10th Administrative Judicial Region, which basically encompasses almost all of northeast Texas. “For example, Travis County, El Paso County have provisions with their sheriff's department where they can automatically make sure those weapons or ammunition are turned over. That does not exist in most of the rural counties that I have.

“When the law says that you're not supposed to possess a firearm or ammunition, if you're under a protective order, then there needs to be some clear cut mechanism or clear mechanism for that to be enforced,” Charles said.

In 2020, according to the Texas Office of Court Administration 26,685 protective orders have been issued in Texas.

While an official state statistic, one domestic violence expert told KHOU 11 she believes the actual number of all types of protective orders issued in this populous state to be higher, based on the numbers of survivors receiving protective order legal advocacy and representation from state domestic violence programs and legal services. One reason for this disparity, she said, was the inconsistent reporting of protective orders to the state by various counties.

In all of 2020, 91 guns have been surrendered to law enforcement, according to the seven sheriff’s offices that provided us their statistics.

“I have had people ask me or make the comment that, ‘If you take away my gun, I can't protect myself.’ Well, what I have to say to that is, fine, don't beat your wife in the first place. Don't commit a crime that would keep you from having a gun,” Langbein said.

El Paso County

2019, Aug-Dec.

- 16 gun surrender orders; 14 total guns

- 12 guns surrendered to law enforcement;

- 2 guns surrendered or sold to third parties; and

- 2 AK/AR type guns surrendered

2020

- 17 gun surrender orders; 31 total guns

- 24 guns surrendered to law enforcement;

- 7 guns surrendered or sold to third parties;

- 4 AK/AR type guns surrendered

No gun surrender orders have been entered thus far in 2021.

Harris County

2018: 1 order and 1 firearm surrendered

2019: 10 orders and 27 firearms surrendered

2020: 13 orders and 25 firearms surrendered

2021: No court orders or firearm surrendered as of this date

Total: 24 orders and 53 firearms surrendered

Dallas County

2015: 24 weapons received

2016: 37 weapons received

2017: Dallas County Gun Surrender Program duties taken over by the Dallas County Sheriff's Department Gun Range; 12 weapons received, 18 released

2018: 23 weapons received, 37 released

2019: 30 weapons received, 32 released

2020: 33 weapons received, 1 released

Kaufman County is working on implementing a protocol, as is Bexar County. Bexar County has been working on the issue for the last year and a half through its Collaborative Commission on Domestic Violence that created a Firearm Transfer Committee. The committee has been coming up with a comprehensive way to deal with domestic violence, including putting a gun surrender protocol in place, according to Judge Monique Diaz, a Civil District Court Judge and the Co-Chair of the Collaborative Commission on Domestic Violence.

“Various courts have long been utilizing their own processes to ensure individuals are complying with orders prohibiting possession of firearms or ammunition, however, those cases have historically not been tracked through a centralized process,” Judge Diaz wrote to us. “One of our goals is to improve the tracking of those cases and the total count of firearms and ammunition turned over through the collaborative work of our Firearm Transfer Committee.”

Loraine Efron, a criminal defense attorney in San Antonio who’s worked on domestic violence cases and is the immediate past president of the San Antonio Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, said the program such as the one being worked on in Bexar County is misdirected and uninformed.

“People are being ordered to dispossess themselves of weapons before they're being convicted of anything, before they're having been found to have committed any family violence,” said Efron. “The weapon is taken from the hands of the citizen who's been accused and puts it into the hands of the government. That's a basic infringement on the Second Amendment right to an individual's right to bear arms. It is going to bottleneck the judicial system, because now you're going to create all kinds of hearings and all kinds of additional litigation with reason relating to the firearm, to the surrender of the firearm.”

“The gun is not the problem, as far as I'm concerned. It's the person, you know,” said Parnell McNamara, Sheriff in McLennan County.

KHOU 11 interviewed Sheriff McNamara in his Waco office in early 2020, right before the pandemic.

“The state system is so weak and that's what makes us all is police officers just sick,” McNamara said. “And we see these protective orders. You know, they sound good on paper. The judges mean well, but they fall short. Some of them aren't worth the paper they're written on because the guy that is set on harming someone could care less.”

In early 2020, we asked Sheriff McNamara if his department had a gun surrender protocol in place for domestic violence protective order respondents to relinquish their weapons.

“We've talked about it and discussed it. And at some point, we may get one,” Sheriff McNamara said. “But right now, we don't have anything in place where people can turn in their guns.”

“I have to be honest; do I have a lot of faith in that working? No, not really,” he added. “But it's worth a try, and we will give it a try.”

KHOU 11 followed up with the sheriff a year later, in January of 2021.

Sheriff McNamara said his office hasn’t implemented a gun surrender protocol for protective order respondents. He said the courts have not ordered any guns turned over to his office. The sheriff told KHOU 11 his office will comply with an order should one come and take the firearm for safe keeping.

We reached out to the judges in McLennan County who deal with family domestic violence cases but haven’t heard back.

Samantha said she’s learned a lot since she left her abusive relationship. She’s a survivor, not a victim.

“My life changed, you know,” she said. “That's why education is so powerful.”

“I know this sounds crazy. I did not realize that I was in an abusive relationship,” she added.

“Samantha,” who’s always been around guns and knows how to use them, believes everybody has the right to protect themselves.

She said the protective order in her case did little to stop her ex-husband.

“I guess maybe I thought that it would deter him,” she said about getting a protective order in the first place. “But it only just made him mad and made him violate it. I think he did it just to spite me and he did it just to spite the law because he knew he could.”

She said laws only bound people who were law abiding, who respected boundaries.

“If you're asking me if I think that they should tell the person who has a protective order, they should relinquish their guns? Do you think they're going to do it? They might, they might give them one or two of them, but what about the other 15 they have?” she said. “There's no way to enforce it.”

Several Texas lawmakers intend to try this legislative session. Representative Joe Moody, a Democrat from El Paso, which has a program, filed a bill suggesting counties come up with their own task forces to figure out how to enforce the gun possession prohibition for domestic violence protective order respondents upon the receipt of the protective order.

“The judge just shouldn't be signing an order that's meaningless,” Rep. Moody told KHOU 11.

In the previous legislative session two years ago, the same bill faced opposition and didn’t go anywhere.

“The proposal was to ensure that the county had a program to enforce protective order laws, that if firearms are to be surrendered because a protective order has been entered then the county should have a system by which they can enforce that protective order,” Rep. Moody said.

In 2018, The House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence, report and recommendations for the 86th Texas Legislature, chaired by Moody, suggested fixes to protective order enforcement.

“Our existing protective orders need statutory enforcement mechanisms to be effective,” the report said. “The law should specify who can seize and store weapons, how and when they’re returned, and how long they must be held if unclaimed for an extended period after restoration of rights. Options should be broad and cost-effective, making use of public-private partnerships if appropriate.”

“Why wouldn't we want it to keep people safe? Why wouldn't we want to address it in this very narrow way?” Moody told KHOU 11.

“The problem that I have is, (it’s) 85 percent the ridiculous nature of it, the fact that it's a waste of time, and only 15 percent infringement,” said David Amad, Vice President of Open Carry Texas, a second amendment gun rights organization. “There is definitely a potential for abuse of these things and for this this little system they want to set up to be misused. And the end result of that being someone's gun rights getting stomped on. But that's a small part of my objection to this stuff. My main objection to it is it's pointless. It's not going to accomplish anything. It's easy to go around it, underneath it, over it or through it. It's not going to do what they want it to do.”

Amad reviewed Moody’s original bill from two years ago, when KHOU 11 first started working on the story in late 2019, early 2020. When contacted by KHOU 11 in 2021, Amad said his position hasn’t changed.

“There's nothing wrong with having sensible laws, but a law that makes you defenseless and unable to to protect yourself is not sensible now, is it?” Amad said. “At the end of the day, when someone attacks you, there's only you and that attacker there. There's no police officer in your pocket. Well, you'd better be able to defend yourself. And a gun is your self-defense equipment. And that's why we want to expand gun rights.”

Amad said if a person wanted to hurt someone, he or she will find a way. There is nothing stopping them.

“The problem is you can’t get the guns out of the hands of bad guys any more than you can get the weed out of the hands of college students,” he said. “They've been trying to do that for half a century. It hasn't worked. If somebody wants to get their hands on something, they're going to get their hands on it, even if they have to build it themselves.”

“The best way to deal with a woman who's getting beaten by a man is to teach her how to defend herself and give her the equipment she needs to actually get the job done,” Amad said.

"Our position is that people on both sides of the spectrum need to stop being so full of themselves and we need to come together and be willing to come to an agreement on what is good public policy with regard to firearms,” wrote Kevin Lawrence, Executive Director of Texas Municipal Police Association in an email to KHOU 11. “TMPA believes in the second amendment. But the right to bear arms is not "an unfettered right." We believe in good, decent law-abiding citizens owning guns and being able to protect themselves. We also believe there are some classes of citizens who should be prohibited from possessing or owning firearm -- for example convicted felons and toddlers. When a court determines there is a danger of domestic violence to the degree a protective order is necessary, it would make sense that the judge should also have the authority to prohibit the accused offender from having access to firearms until the case has been properly adjudicated.”

A domestic violence survivor, who wanted to be named “Zoe,” and asked KHOU 11 not to show her face for safety reasons. Zoe said she wasn’t anti-gun, but some people shouldn’t have access to them.

She said her abusive ex-husband collected firearms and ammunition.

“He believed World War III was imminent, and he always claimed he was out to protect himself with a couple of children in the house,” she said. “He would amass large quantities of ammunition, the high capacity magazines, and then both handguns and long guns.”

After many years of abuse, she left him.

“Over the years, I became very sure that he could kill me if he wanted to. He said he would. He threatened to do it many times, and he certainly had the ability to do so,” Zoe said.

“After he was under the protective order, he removed all the guns, the ammunition, the reloading equipment, the magazines, the gun safe,” she said. “I was surprised, because he was under protective order and not allowed to have any of these items.”

Zoe told KHOU 11 if the laws were on the books, it made sense they were enforced.

In Texas, if a person, while being a subject of a protective order, is contacted by police and is found to have a weapon, the person picks up an extra charge.

Advocates like Zoe are pushing for gun possession prohibition enforcement during the first steps of issuing a protective order that outlines what a respondent can’t do.

“The vast majority of jurisdictions across the state don’t have gun surrender protocols in place to take firearms from domestic violence offenders or anyone else who’s prohibited from having a firearm,” said J. Staley Heatly, District Attorney for Wilbarger, Hardeman and Foard Counties, who’s also TCFV’s co-chair of the Public Policy Committee. “There isn’t any specific provision in the law that places that responsibility on a certain agency or party, it’s not clear if it’s the role of the judge, the sheriff, the police or a prosecutor. Because of that- nothing happens. That is why we need legislation to address this issue.”

“We should still attempt enforcement, even if we can’t have perfect enforcement,” said Abby Frank, managing attorney who runs the Crime Victims Litigation unit at Texas Legal Services Center. “The available research shows that protective orders are effective in decreasing intimate partner violence. Firearms surrender programs are the best practice because they provide immediate protection for the victim and immediate accountability for the perpetrator.”

“I think it's worth a try,” Zoe said. “And see if we can have a safe surrender system where those guns can be put away while the person is under a protective order.”