NEW ORLEANS — Former Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco, Louisiana’s first female chief executive, whose one term in office was dominated by criticism of her response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, died Sunday, Aug. 18. She was 76.

In December 2017, Blanco, who had undergone treatment six years earlier for an ocular melanoma, revealed the rare, incurable type of cancer had spread to her liver. At the time, she said doctors told her she may have only six months to live. She underwent treatment for 16 months but in April 2019 entered hospice care.

“I am in a fight for my own life. One that will be difficult to win,” she wrote in a letter published in 2017 in newspapers statewide. “I knew from the start of my cancer journey this could happen, but with each passing year, I hoped this cup would pass me by. It did not.”

One year later, in December 2018, the former governor said that while she remained optimistic, she understood there was “no escape. The monster is not far down the road.” She spoke before a gathering of the Council for A Better Louisiana, which gave her an award for distinguished service.

One of her final public appearances was in July 2019, when she was honored with the naming of a section of U.S. Highway 90 in Lafayette in her honor. She appeared frail at the ceremony, where she said she was touched by the signs of love and respect for her in her final months. “This has been a wonderful time for me even though it’s a time of my countdown,” she said. “All of us think they’d like to die peacefully in their sleep, but let me tell you when people have a chance to make up…that’s a remarkable way to go.”

A family member confirmed Blanco passed away peacefully, surrounded by her family, at the St. Joseph's Hospice Carpenter House in Lafayette.

"She was a woman of grace, faith and hope. She has left an eternal mark on all who knew her, because she was generous and unconditional in her love, warm in her embrace and genuinely interested in the welfare of others," an official statement from the family said.

In June, she was honored by the New Orleans Saints Hall of Fame with the Joe Gemelli Fleur de Lis award for her contributions to the New Orleans Saints organization.

Article continues under video. Can't see it? Click here

The news about her health drew an outpouring of support for the former governor, whose career in state and local government kept her in the public eye for more than 30 years. That included two terms in the state legislature, two terms on the Public Service Commission and two terms as lieutenant governor. Blanco made history when she defeated Bobby Jindal in 2003 to become the first female governor in Louisiana’s history.

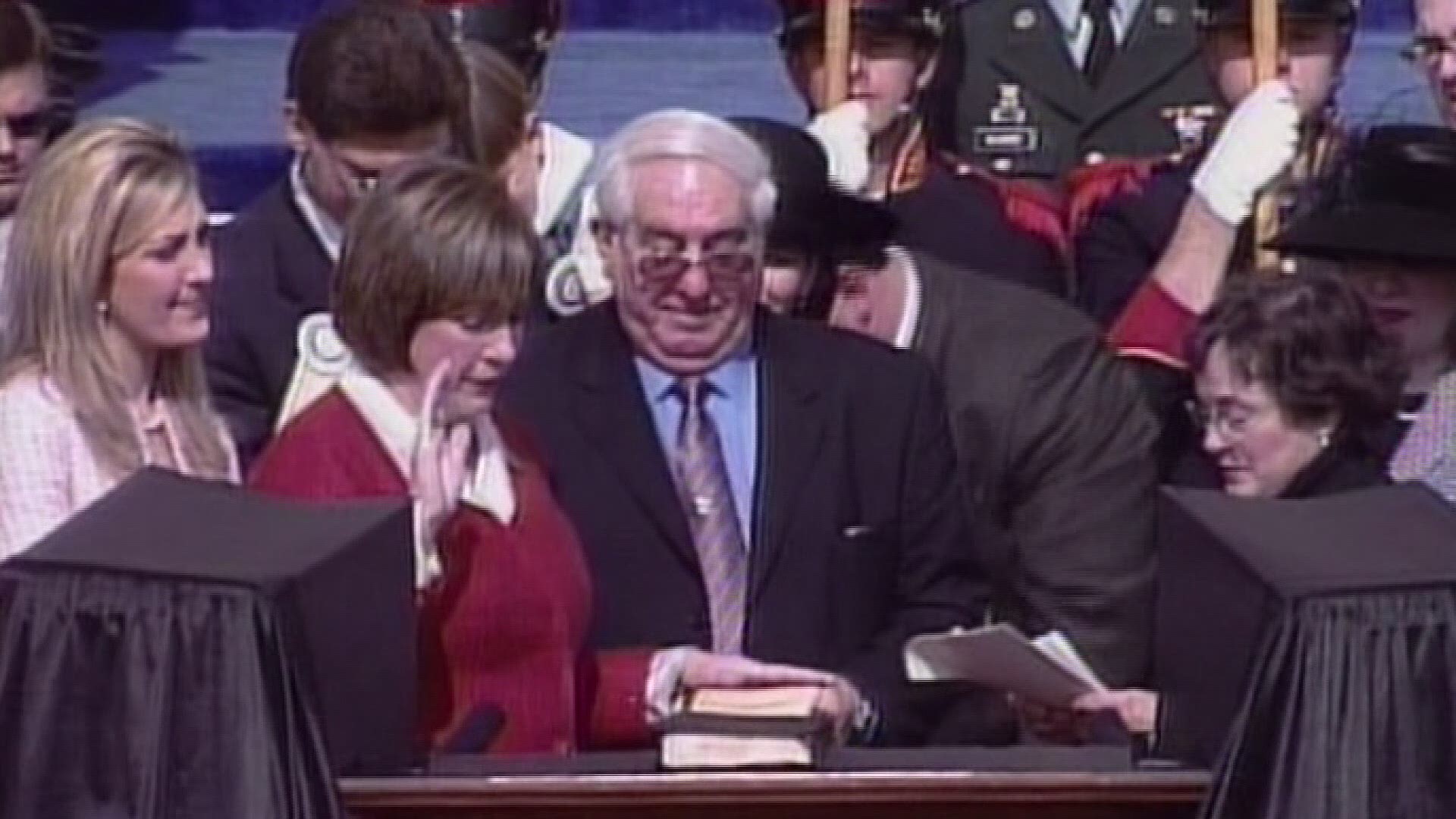

Blanco’s term began with her taking the oath of office in English and French, a nod to her Cajun-French heritage. In her inaugural address, she promised a new kind of government, saying she would work to expand business opportunities in the state and repair the public health care system.

"It’s extraordinary that this opportunity should come my way, but we all know that it’s a sign of our state’s strong desire for leadership, for a new kind of government in Louisiana – one that is open, progressive and accountable to its people," she said. "This is the kind of government I intend to give to you."

Eighteen months after her inauguration, Hurricane Katrina and the federal levee failures would devastate much of the New Orleans area and consume the remainder of Blanco’s first term.

Katrina, the largest natural disaster ever to hit the United States, sent Blanco and her administration into full crisis mode. Hurricane Rita would bring major flooding, storm surge and wind damage to south Louisiana only a month later.

Though Blanco’s administration oversaw the successful evacuation of 93 percent of residents in the Katrina flood zone during non-stop rescues in the initial days after Katrina, she was widely criticized for her handling of the disaster response. She cried on national television, which some critics interpreted as a sign of weakness.

Article continues under video. Can't see it? Click here

Blanco, a Democrat, would later criticize then-President George W. Bush, his political adviser Karl Rove and other Republican officials for playing politics with the state’s recovery and not quickly sending the resources the state badly needed.

"These individuals based key decisions of emergency response on the gender and party affiliation of elected officials, rather than the urgent needs of our people,” she said in 2007. “I don't think he (Bush) intended anything bad to happen to anyone. But I do think there were people in his cabinet who (while) trying to save his face, started pointing fingers at Louisiana,” Blanco said.

When President Bush released a memoir in 2010 and chronicled his administration’s Katrina response, the nasty political fight further came into view. He criticized Blanco for not agreeing to federalize the Louisiana National Guard. Blanco argued that doing so would have taken police power away from guardsmen, something she said could not happen during a period of such lawlessness.

In the months after the hurricane, Blanco traveled nine times to Washington, D.C. to personally advocate for federal recovery money for the state, pointing out the disparity in assistance received by Louisiana compared to neighboring Mississippi.

“I told Andrew Card, who was the president's chief of staff, ‘We're not going to tolerate that.' You live in the wrong state … same hurricane, wrong state, you get twice as much in Mississippi? I don't think so,” she told WWL-TV in a 2013 interview.

As more than $13.5 billion in federal housing aid later poured into the state, Blanco and her administration would establish the Road Home program, the biggest housing recovery effort in American history.

The program, which bore Blanco’s name, was designed to be nearly impervious to fraud by fingerprinting applicants and paying grants like home construction loans. Despite that, fraud did exist, and the program’s slow pace crippled many homeowners’ recovery.

Blanco later said she didn't launch Road Home until almost a year after Katrina because she wanted to give grants to every damaged home in the state, flooded or not. She was roundly criticized for designing a program that paid grants based on pre-storm values, rather than the cost of actually rebuilding, something a federal judge later declared was likely discriminatory toward black residents.

“We tried to address every concern and it's next to impossible to address every single concern,” she said.

In a 2013 WWL-TV interview, she added that the White House orchestrated a change in March 2007 meant to damage her politically: the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development said the state was wrongly requiring homeowners to wait for reimbursement rather than giving them the option of taking a lump sum compensation payment.

A week after that decision, Blanco bowed to political pressure and dismal poll numbers and announced she would not seek re-election to a second term.

"Since Katrina and Rita, I have devoted every waking hour to the recovery and to making the entire state stronger. Of course, there have been those who have attempted to exploit these tragedies for partisan gain. This is wrong,” she said during her announcement. She said she would devote the remaining nine months of her term to speeding up the state’s recovery. "We have no time to look back," she said.

One recovery effort for which Blanco would later receive credit was her decision to push for the renovation of the Louisiana Superdome, renamed the Mercedes-Benz Superdome in 2011.

Used as a shelter of last resort during the storm and severely damaged by high winds, many thought the building would never return to its former glory. There were also questions about whether the New Orleans Saints would even return to the facility, with team owner Tom Benson flirting with the idea of relocating the football team to San Antonio.

“It was a very challenging decision for me to make in the midst of all kind of grieving going on and all the destruction. As governor I felt like I had to look ahead. I had to see a future when everybody was working in the present,” she told WWL-TV in 2015. “The dome itself had become the total symbol of despair. Every bit of it was ruined.” Members of the state Legislature and some citizens criticized her for having the wrong priorities. After $185 million in repairs, the Superdome reopened on Sept. 25, 2006, with an emotional 23-3 Saints’ victory over the Atlanta Falcons.

“I made a tough decision, got a lot of apologies after that first (Saints) game. It was the best thing we could have done for the people who were working in the trenches who had been working so hard and suffered so much over the prior year,” she said of the Superdome’s reopening. “And you know everybody needed that mental relief. They needed to know that something that big could be done and be done well and that we could have successes.”

Kathleen Babineaux was born Dec. 15, 1942, in Coteau, a small settlement in Iberia Parish south of Lafayette. The eldest of seven children, she grew up in a devout Roman Catholic family and attended Mount Carmel Academy, a Catholic girls school in New Iberia.

In 1964, Blanco received a bachelor of science degree in business education from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, then named the University of Southwestern Louisiana. That same year, she married Raymond “Coach” Blanco, who gained fame in the region for leading Catholic High School in New Iberia to a state football championship two years earlier.

Early in their marriage, she taught business courses at Breaux Bridge High School but then became a stay-at-home mom for the couple’s six children: four daughters and two sons.

In 1980, she took a job as a district manager with the decennial census and soon after she and her husband formed a political consulting and polling firm, turning one of their hobbies into a business. In 1983, she took things a step further, running for an open seat in the Louisiana House of Representatives.

“I had no political ambitions but I thought to myself, ‘I’m going to do public service, where I’m not going to make a lot of money and get rich, but it will be personally fulfilling and rewarding,’” she told LaPolitics.com for an Aug. 2018 profile.

Blanco ran a small, door-to-door campaign and pulled off an upset, becoming the first female legislator from the city of Lafayette. She was one of only five women serving in the state Legislature at the time.

In 1988, she was elected to the Louisiana Public Service Commission, the independent state body which regulates public utilities and motor carriers. Before Blanco, three men – Huey P. Long, Jimmie Davis and John McKeithen – had served on the PSC before being elected governor. “The minute you get onto the Public Service Commission in Louisiana people assume that you’re going to run for governor,” she told LaPolitics.com. “I thought that was so uniquely bizarre because that was never my intention. I didn’t have that vision of me being the governor at that point in time.”

Despite that, she would in three years decide to enter the gubernatorial primary, staying in the 1991 race for only 100 days before bowing out of a campaign that would ultimately pit David Duke against Edwin Edwards.

The governor’s office would not be hers that year, but five years later she won the statewide post of lieutenant governor, succeeding Melinda Schwegmann, the first woman elected to that office. Like previous officeholders, Blanco focused on the state’s museums and tourism industry. She easily won a second term with 80 percent of the vote.

In 2003, she once again entered a crowded field of 18 candidates for governor which included a former governor, the state attorney general, state Senate president and several other former high-ranking state legislators. It would also include 32-year-old Bobby Jindal, the state Secretary of Health and Hospitals and a protégé of departing Gov. Mike Foster. Jindal earned nearly 33 percent of the vote in the primary, with Blanco far behind at 18 percent.

In the runoff campaign, Blanco’s team ran commercials attacking Jindal’s record as health secretary and lack of political experience. An eleventh-hour turning point came during the final statewide televised debate, hosted by WWL-TV.

In the final question, both candidates were asked by moderator Dennis Woltering to name the most defining moment in their lives. Blanco nearly came to tears as she recalled the death of her son, Ben, who was killed at age 19 in an industrial accident. She said she gained "inner strength and inner peace" by learning to cope with the grief and pulling her family together after her son’s death.

"My defining moment was to know that I can survive it, and to know that the people of Louisiana are there to lift me in prayer," Blanco said.

Many political watchers felt the response endeared her to voters, particularly women, catapulting her to a 52-48 percent win over Jindal in the runoff. She carried her native Acadiana and trounced Jindal in the New Orleans area.

"The people of Louisiana have spoken," Blanco told supporters at her victory party in Lafayette on election night. "We have sent a new message out to the nation: that this is a new Louisiana."

Survivors include her husband of more than 53 years; five children; 13 grandchildren; her mother and five siblings.