Edwin Edwards, the colorful and controversial four-term former governor of Louisiana whose federal conviction and 10-year prison sentence earned him a national reputation for corruption died Monday. He was 93 years old.

A statement from his spokesman and biographer Leo Honeycutt said Edwards died peacefully at his home in Gonzales with family and friends by his bedside.

In the statement, Trina Scott Edwards - the former governor's widow and mother of his fifth child, who will turn eight on Aug. 1 - said, “His last words were to Eli. Eli told him every night, ‘I love you.’ And he told Eli, ‘I love you, too.’ Those were his last words.”

“I have lived a good life, had better breaks than most, had some bad breaks, too, but that’s all part of it," were also among Edwards' last words, according to Honeycutt. "I tried to help as many people as I could and I hope I did that, and I hope, if I did, that they will help others, too. I love Louisiana and I always will.”

On July 5, Edwards and his wife Trina announced that he had entered hospice care, though no specific details were given about his condition. “Since I have been in and out of hospitals in recent years with pneumonia and other respiratory problems, causing a lot of people a lot of trouble, I have decided to retain the services of qualified hospice doctors and nurses at my home,” Edwards said in a statement. “I’ve made no bones that I have considered myself on borrowed time for 20 years and we each know that all this fun has to end at some point.”

During the coronavirus pandemic in Nov. 2020, Edwards was hospitalized with what were described as breathing problems, later diagnosed as pneumonia. Although the former governor had other health scares in recent years, friends and family said he remained mentally sharp and active well into his 90s.

In Monday's statement, Anna Edwards, the ex-governor's oldest child, said, “I am heartbroken at the loss of my father. He was a profound influence in my life and I will always miss him. His passing will create a huge void, but I sincerely thank everyone who expressed love and concern. He touched the lives of many fellow Louisianans and I know he will be remembered with great fondness.”

His son Stephen Edwards, who worked alongside his father in the Edwards Law Firm, said, “My dad never saw color and never turned his back on anyone in need. He helped all, especially me. He was an infallible pillar of strength but he kept a piece of tremendous pain for the rest of his life for the murder of his baby brother Nolan. Dad’s successes made him a legend but his losses made him human and his humanity made him easy to love. Louisiana has lost the love of its life."

Edwards, whose nicknames included “the Cajun Prince,” “the Silver Fox,” “the Silver Zipper” and “Fast Eddie,” was a charismatic, colorful and politically savvy figure. He dominated state politics during the final three decades of the 20th century, and history no doubt will note the irony of Edwards running as a “reformer” in his first bid for governor, in 1971.

Four-time governor

Fast with witty retorts and clever one-liners, the Democrat served as Louisiana governor for an unprecedented four terms – from 1972 to 1980, 1984 to 1988 and 1992 to 1996.

His 1991 victory over neo-Nazi and Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke – when a bumper sticker famously encouraged people to “Vote for the Crook - It’s Important” – made international headlines.

On the heels of that victory, Edwards promoted and set up the mechanism to approve legalized casino gambling in Louisiana. In a twist of fate, his alleged role in the award of riverboat casino licenses in 1997 — after he left office for the last time — led to his indictment and conviction on racketeering and corruption charges.

While Edwards developed a reputation for corruption and cronyism, womanizing and high-stakes casino gambling in Las Vegas, he was one of the shrewdest and most politically capable leaders in state history.

During his 16 years as governor, he led the push to draft and adopt the state’s 1974 Constitution, championed civil rights and social services programs, modernized oil and gas taxation and boosted the state’s rainy day fund.

Edwards’ political career, though interrupted by a jail term, spanned six decades. It began with his election to the Crowley City Council in 1954, followed by a one-year stint in the Louisiana State Senate in the mid-1960s and seven years in the U.S. House of Representatives. He served four terms as governor between 1972 and 1996. His political career ended in a failed political comeback for Congress in 2014.

Conviction

Long dogged by allegations of skirt-chasing and corruption and tried three times on federal charges, Edwards was convicted in May 2000 for his role in a racketeering scheme involving state riverboat casino licenses. He was found guilty of extorting nearly $3 million from companies that applied for casino licenses during his last term in office.

A federal jury deliberated for nine days before finding Edwards guilty on 17 counts of racketeering, mail and wire fraud, conspiracy, and money laundering. His son, Stephen, and five other men were also convicted in the same trial.

The bribery scandal likewise cost then-San Francisco 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr., a friend of Edwards’, his ownership of the NFL team. DeBartolo said he gave Edwards a briefcase stuffed with $400,000 in cash in hopes of getting a riverboat casino license. DeBartolo pleaded guilty to a charge of failing to report a felony and received a $1 million fine and two years of probation in return for his testimony against Edwards, saying the cash was an extortion payoff.

The charges against Edwards brought a maximum sentence of almost 350 years in prison. He brushed aside that possibility with his usual mix of candor and humor: "I can truthfully say if my sentence is 350 years, I don't intend to serve,” he quipped. He was eventually sentenced to 10 years in prison.

After jurors returned a guilty verdict, a somber Edwards said on the courthouse steps, "The Chinese have a saying that if you sit by the river long enough, the dead body of your enemy will come floating down the river. I suppose the feds sat by the river long enough, so here comes my body. I regret that it has ended this way, but that is the system. I have lived 72 years of my life within the system, I'll spend the rest of my life within the system. Whatever consequences flow from this, I'm prepared to face."

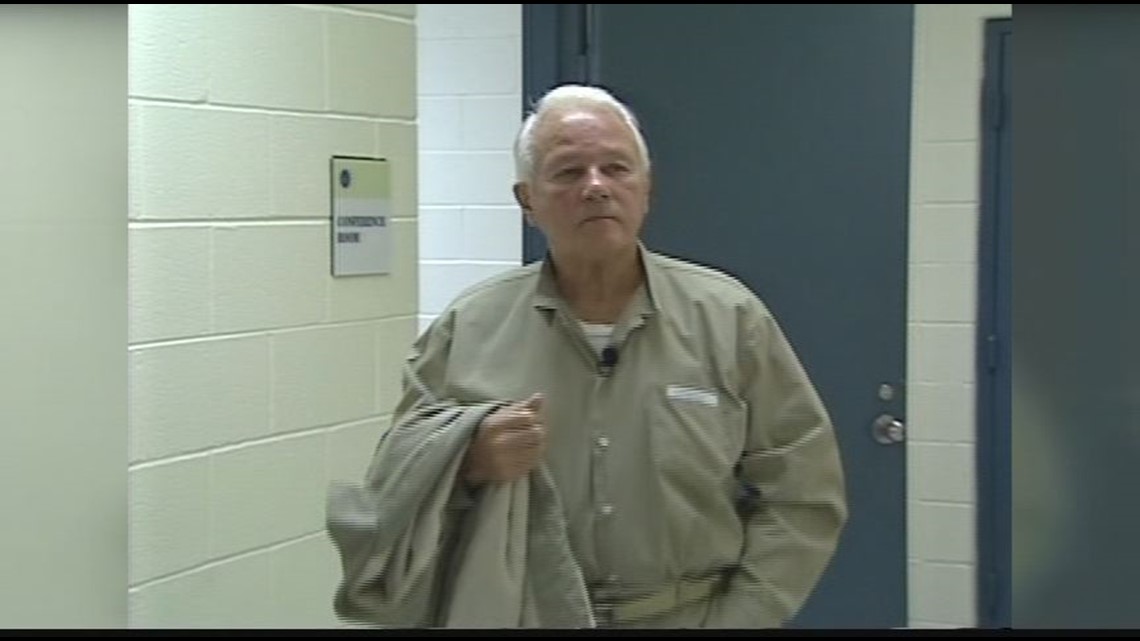

While appealing his conviction, Edwards reported to federal prison in 2002, spending eight years in prisons in Fort Worth, Texas, and then Oakdale, Louisiana, as well as six months in home detention and three years on probation.

All the while, Edwards maintained he had been railroaded by presiding U.S. District Judge Frank Polozola, whose removal of a juror – known as Juror 68 – formed the basis for the former governor’s later appeal.

Because Polozola removed Juror 68 days after jurors began deliberating, Edwards’ conviction, which by law had to be unanimous, came at the hands of 11 jurors, not the usual 12. Appellate courts declined to overturn that verdict. Juror 68 later said he was intimidated by other jurors because he expressed doubts about Edwards’ guilt.

Despite the conviction, Edwards said he was not bitter. “I’ve had so much undeserved good luck in my life that I decided that I can accept undeserved bad luck, which is what it was,” he said. “I didn’t whine or cry or plead, I just walked into prison…and made up my mind I would do what was necessary to walk out, and that’s what I did.”

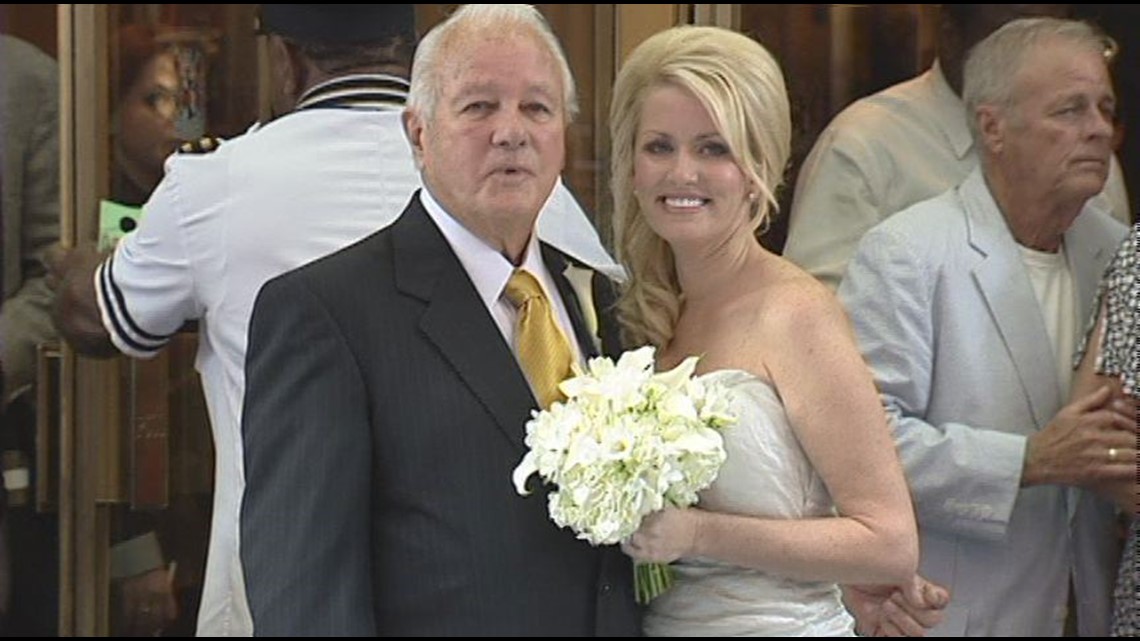

He was released from prison in 2011. That same year, at age 83, he married his third wife, Trina Grimes Scott, then 32, who had visited him in prison after they struck up a pen pal relationship.

“They sent me to prison for life and I came out with a good-looking wife,” Edwards joked.

That year, the couple had a son, Edwards’ fifth child, Eli. They also starred in a short-lived cable TV reality show, “The Governor’s Wife.” It was canceled after only a few episodes.

Early Life

Edwin Washington Edwards – often referred to by his initials, EWE – was born Aug. 7, 1927 in rural Avoyelles Parish, in the community of Mansura, just outside the central Louisiana town of Marksville. Edwards’ father was a sharecropper and his mother, the local midwife.

Edwin, the couple’s third child, was born the year of the Great Flood of 1927 which devastated central and south Louisiana, leaving thousands homeless. The Edwards family lived on a natural ridge which made Marksville essentially an island.

The Edwardses survived the flood but had to also endure the Great Depression. In his 2009 authorized biography, written by Leo Honeycutt, Edwards recalled working on his family’s farm and even picking cotton to help his family.

Edwards remembered traveling with his father at age seven to hear a speech by then-U.S. Senator Huey P. Long, also the state’s former governor. As it turned out, Long’s “Every Man a King” mantra shaped the political philosophy Edwards would adopt years later. “Serve the needy, not the greedy,” is how Edwards later described it.

Initially, Edwards saw preaching, and not politics, as his future. Though baptized a Catholic, at age 14 he converted to the Church of the Nazarene, an Evangelical Christian denomination to which his maternal grandmother belonged. He became a youth minister and, according to Honeycutt, refined the oratory style he later used in campaigning. He reportedly told his teenage sweetheart, Elaine Schwartzenburg — who later became his first wife — that he would be governor one day.

As a young preacher and student at Marksville High School, he also learned to employ humor in his sermons and daily life, which made him popular. He was elected president of his senior class.

LSU, U.S. Navy and Law School

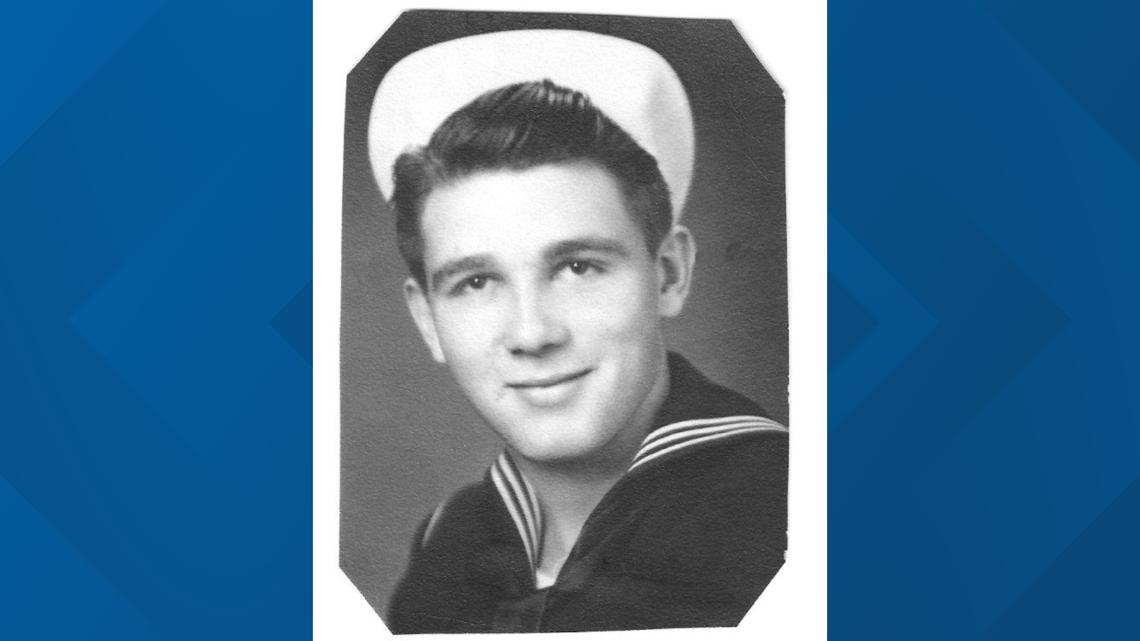

Edwards enrolled in Louisiana State University after graduation but left in 1945 to enlist in the U.S. Navy as World War II was coming to an end. He returned home and enrolled in LSU law school, becoming a lawyer at age 21.

Fresh out of law school and looking for work, Edwards followed his sister Audrey to the southwest Louisiana city of Crowley, where she and her husband had been recruited to lead a Nazarene church. She encouraged her brother to start his practice there, noting that there were few French-speaking attorneys in that area.

While settling in Crowley, Edwards also married Schwartenzburg. Like Edwards, she was a native of Avoyelles Parish. To marry her, Edwin Edwards converted back to Catholicism. The couple wed in 1949. The first of their four children, Anna, was born in 1950.

After building his law practice, Edwards launched his political career in Crowley. He ran for City Council in 1954, with Edmund Reggie, a city judge who later became a confidante of John F. Kennedy, serving as his campaign manager. Edwards won the election and served for 10 years before being elected to the state Senate from Acadia Parish in 1964.

In 1965, just one year into his term in the state Legislature, Edwards ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in a special election called to fill the seat of Rep. T.A. Thompson, who died in an auto accident.

“I didn’t really want to go to Washington,” Edwards said in his biography. “Thompson’s death was a detour in my political plans. I had planned on staying in the Senate until (Gov. John) McKeithen retired and then run for governor.”

Although he served in a delegation which included heavyweights like Hale Boggs, Russell Long, Allen Ellender and F. Edward Hebert, Edwards said he found his time in Washington boring and unproductive.

First run for Governor

By 1971, with McKeithen term-limited as governor, Edwards plotted his return to state politics and a run for Louisiana’s highest office.

“My desire to run was heightened by the fact that a Cajun fellow had no chance to be in the governor’s office and that the guy from South Louisiana always got defeated by the guy from North Louisiana,” he wrote in his biography. “While I didn’t want to divide the state, I just thought that it was time for us to look realistically at the possibility of a southern candidate.”

Political watchers considered Edwards a longshot in a race which became a free-for-all, with 17 Democratic candidates in the primary, including Lt. Gov. C.C. “Taddy” Aycock, former Gov. Jimmie Davis, supermarket magnate John G. Schwegmann and several state lawmakers, including J. Bennett Johnston and Republican newcomer David Treen, who faced token opposition in the GOP primary.

During the campaign, Edwards promised to bring more Blacks into state government and vowed to name more minorities to state boards and commissions. It was a risky move in what was still a slowly-desegregating state, but the stance won Edwards widespread support among Black voters.

In the closest gubernatorial primary in state history, Edwards narrowly defeated Johnston and advanced to the general election, where he defeated Treen by more than 160,000 votes.

The fact that he had to endure two grueling Democratic elections before facing a well-rested Treen in the general election stuck in Edwards’ craw. He convinced state lawmakers to adopt a non-partisan or “open” primary system in which all candidates, regardless of party affiliation, run against each other. If no one garners a majority, the top two finishers, regardless of party, face off in a general election. That system is still used in Louisiana today. On inauguration day, May 9, 1972, with his brother Nolan officiating, Edwards took the oath of office twice – once in Cajun French and a second time in English – to become the 56th governor of Louisiana.

Mover and Shaker

During his first term, he led the April 1974 campaign to secure voter approval of a proposed new state constitution, which replaced the clunky, longest-in-the-nation 1921 state charter. The new constitution, written in 1973 and early 1974, took effect in 1975 and directed the governor to reorganize the executive branch — another of his campaign promises. When implemented, the new constitution gave Louisiana its first "cabinet style" executive department, replacing the hundreds of boards and commissions that had existed for decades.

Edwards also pushed for legislation tying the severance tax on crude oil to a percentage of the barrel price rather than a flat fee. High energy prices in the 1970s swelled state coffers and helped Louisiana maintain a balanced budget during Edwards' first two terms.

Though he enjoyed success in office, signs soon emerged of the kind of ethical lapses that would dog him for years. In his first term, following explosive allegations by Edwards’ onetime confidant and bodyguard Clyde Vidrine, state grand juries investigated whether Edwards sold high level state jobs for political contributions. He never faced any state charges, however. Vidrine would later write a tell-all book about his alleged exploits with Edwards, titled “Just Takin’ Orders: A Southern Governor’s Watergate.”

Despite persistent ethical questions that surrounded Edwards, many voters came to love his flamboyant style. Stories of his womanizing became legendary, and he made no secret of his regular visits to Las Vegas casinos. “I gamble for fun because I like it,” he once said in response to a scathing article by States-Item reporter Bill Lynch criticizing the governor for his gambling trips. “If you feel good about it, you do it and if you don’t and you’re smart, then you don’t. Cities are not sinful, trips are not sinful, people are sinful.”

Easy re-election

In 1975, Edwards spoke at the dedication ceremonies for the Louisiana Superdome, cutting the ribbon on the $163 million facility whose creation was spearheaded by his predecessor, Gov. John McKeithen. That same year, Edwards easily won re-election to a second term with 62 percent of the vote. Louisiana’s economy, buoyed by the oil boom, was riding high and the good times were rolling for the Cajun governor.

At the beginning of his second term in 1976, The Washington Post linked him to a ring of South Korean agents who allegedly bribed twenty congressmen. The newspaper reported that Korean businessman Tongsun Park had given money to a New Jersey congressman, a California representative and $10,000 to “a relative” of Edwin Edwards.

At first, Edwards admitted to making trips to Korea to sell Louisiana rice, but denied taking money. Edwards later testified that when he refused Park’s contribution, Park told Elaine Edwards that he wanted to do something for her and their daughters Vicki and Anna. He gave her a table and an envelope containing $10,000 cash.

Park was indicted for bribery, illegal lobbying and other crimes but later given immunity from prosecutors and admitted to bribing 31 members of Congress. Edwards confidently said he would not be indicted in the so-called “Koreagate” scandal, since he gave nothing to Park in return. Neither he nor his wife or daughters were charged.

Third term

Term limits forced Edwards out of the governor’s mansion in 1980. He was replaced by Treen, who won the 1979 race for governor and became Louisiana’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction. Before long, Edwards was launching a campaign for a third term in the 1983 election.

That year, tragedy struck the Edwards family when Edwin’s brother Nolan, an attorney, was killed by an irate client who fatally shot him inside his law office, then turned the gun on himself. The man, Rodney Wingate Jr., had been pardoned by Gov. Edwards in 1980 for two drug convictions in the 1970s, a pardon procured through the intervention of Nolan Edwards.

Edwards suspended his campaign to bury his brother but was soon back on the campaign trail and in rare form at the election’s televised debates and campaign appearances.

The 1983 race gave rise to two of his most famous zingers. To then-Times-Picayune/States-Item reporter Dean Baquet (who would later become editor of The New York Times), Edwards commented, "The only way I can lose this race is to be caught in bed with a live boy or dead girl."

Of Treen, who was said to ponder laboriously over even minute decisions, Edwards said, “Dave Treen is so slow it takes him an hour and a half to watch ‘60 Minutes.’” Edwards later said he regretted the remark about Treen, who two decades later lobbied then-President George W. Bush to pardon Edwards or grant him an early release from federal prison.

Edwards won the 1983 race in a landslide, defeating Treen in the open primary with 62 percent of the vote. On stage at his victory party at the Hotel Monteleone, Edwards told the crowd, “They tried to indict me, they called me names, they spread rumors about me that were untrue and malicious, but I am glad to have had the jury of the greatest people in the world.”

To retire a reputed $5 million in campaign debts, Edwards famously invited friends and supporters to celebrate his victory via a fundraising trip to Paris. Tickets went for $10,000 per person. The high point of the trip was a formal state dinner at the Palace of Versailles.

“If I can get the Legislature to appropriate the funds, we’re going to build one like this in Louisiana,” he quipped of the opulent palace. Edwards visited Notre Dame Cathedral and encountered a nun from Rayne, Louisiana, who was stationed in Paris. She said she wanted to give him a (two-cheeked) French kiss, to which he deadpanned, “That’s fine, sister. Just don’t let me get into the habit.”

When Edwards took office for a third term as governor in 1984, Louisiana faced a $250 million revenue gap, partly brought on by plummeting oil prices. Additionally, Edwards had to address the financial fiasco of the 1984 World’s Fair. Amid those troubles, he navigated the sale of the New Orleans Saints to Tom Benson in 1985, keeping the team from leaving Louisiana by giving Benson precedent-setting concessions that helped Benson swing the deal financially.

That same year, Edwards was indicted by a federal grand jury on 51 counts of racketeering, wire fraud and mail fraud. He and six others, including his brother, Marion, were accused of conspiring to illegally obtain and sell state hospital licenses.

Edwards proclaimed his innocence and insisted that the charges were politically motivated by U.S. Attorney John Volz, who was appointed in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, but changed his party affiliation to Republican to remain in office during President Ronald Reagan’s two terms.

Edwards’ flamboyant style was on display throughout the 14-week trial. At one point, he arrived at the federal courthouse by mule-drawn carriage, saying he “was looking for some mode of transportation that was indicative of the pace of the trial.”

Another day, he walked backwards down the sidewalk and up the steps of the courthouse, saying he wanted to give a break to press photographers, accustomed to walking backwards to capture images of him as he walked in and out of court. Once, when reporters asked him if he had anything to hide, Edwards responded, “Oh yes, but not in connection with this investigation.”

The long trial ended with a hung jury - 11 jurors voted to acquit, one to convict - and mistrial in December 1985. “I have just won the 16th and most important election of my life,” Edwards told reporters afterwards. “How sweet it is!”

Volz and federal prosecutors retried Edwards and his associates a year later. After that seven-week trial, a jury unanimously found him not guilty of all charges.

Trials take their toll

Although acquitted, Edwards’ reputation took a major hit, making his 1987 re-election campaign much more difficult than his previous runs for office. The field that year included Secretary of State Jim Brown and three of the state’s Congressmen: Bob Livingston, Billy Tauzin and Charles “Buddy” Roemer III, whose father was Edwards’ former commissioner of administration.

Running second in the primary to Roemer, Edwards took to the stage at his election night party at the Hotel Monteleone. Superstitious about his chances, Edwards always had his Election Night parties at the French Quarter hotel after his first statewide win in 1971. On the hotel’s stage that night in 1987, he shocked many by announcing he would withdraw from the race rather than face Roemer in a runoff. “The decision I made is because I want Louisiana to get better,” Edwards told his supporters. That was the first defeat of his political career.

Analysts later said that by pulling out of the race, Edwards set the stage for his return four years later, by denying Roemer an electoral majority and mandate, which Roemer surely would have won in a runoff. Edwards’ withdrawal also saddled the new governor with massive fiscal problems brought on by low oil and gas prices.

A politically wounded Edwin Edwards left office in 1988. He revealed in his biography that he was depressed by the election’s outcome, crying to his wife, Elaine, “I’m not happy. I just can’t make it.”

Second Marriage

Though Elaine Edwards said she did her best to support her husband in his transition to private life, the two had grown apart after years in the spotlight (and Edwards’ infidelity). They filed for divorce in 1989. The next year, Edwards met 26-year-old Candace Picou, who worked as a legal secretary. The two dated for several years and married at the Governor’s Mansion in 1994, during his fourth and final term in office. Then-Louisiana Chief Justice Pascal Calogero Jr. officiated their wedding.

In 1991, Edwards was back in the headlines when he jumped into the race for governor. Eyeing a fourth term, he saw a chance to defeat Buddy Roemer and his self-described “Roemer revolution” method of reforming state government.

It wasn’t Roemer but another candidate who would draw the most attention during the campaign. Instead, it was David Duke, the notorious white supremacist, neo-Nazi and former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard, who won a special election to to the Louisiana House of Representatives from Metairie in 1989.

In 1990, Duke earned 44 percent of the vote in a statewide race against incumbent Sen. J. Bennett Johnston. Though Johnston won, Duke’s strong showing was a sign that he would be a factor in the 1991 governor’s race. On top of that, Duke faced bleak prospects of winning back his state legislative seat in a full-turnout election.

Edwards-Duke

Edwards led the field of candidates in the primary, winning 34 percent of the vote, with Duke close behind at 32 percent. Roemer, the incumbent, earned a disappointing 27 percent. “What’s important is not my past and not Duke’s,” Edwards told his supporters on Election Night. “It’s which of us can best bring stability to Louisiana.”

The Edwards-Duke runoff put Louisiana in the national media spotlight. Edwards kept up his reputation for one-liners during the frenzied campaign, claiming “the only place David Duke and I are alike is we’re both wizards under the sheets.”

Calling the election “the choice of our lives,” a Times-Picayune editorial said “For those who are tempted to sit this one out in disgust or complacency, we repeat: Edwin Edwards, our flawed former governor, is the only alternative to David Duke.”

Edwards would go on to defeat Duke, 61 percent to 39 percent. He earned well over one-million votes, the most of any governor in Louisiana history.

Edwards entered his fourth term in office in 1992 facing a $1 billion state deficit left behind by Roemer, even though he had presided over the legalization of a state lottery, video poker and riverboat gambling. Edwards proposed a land-based casino in New Orleans as a way of generating additional revenue. In 1992, after much debate, he signed into law a bill approving the casino, which opened in 1995.

The next year, after Edwards left office, WWL-TV reported that the FBI planted cameras in the office of Edwards’ Baton Rouge home as part of an investigation into gambling and a range of other business deals. His phone calls were recorded as part of the case, which led federal agents to raid Edwards’ home and office in 1997. The investigation would lead to his indictment on 28 counts in 1998.

“It’s actually less than I expected,” he quipped after the indictment. “I’m not charged with the Oklahoma City bombing.”

Edwards was convicted on May 9, 2000 – exactly 28 years to the day since he was first sworn in as governor in 1972. The man often referred to as “the Teflon governor” appeared to have finally seen accusations stick to him.

Months later, in October 2000, Edwards was acquitted on fraud charges related to the liquidation of the failed Cascade Insurance Company.

While in prison, Edwards worked on his biography and helped his legal team – which included Alan Dershowitz – appeal his conviction. Their appeal to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals focused on the constitutionality of the government surveillance in the case and their contention that Judge Polozola was “hell-bent” on removing the infamous Juror 68 at trial. The 5th Circuit disagreed, as did the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to take up the appeal.

Edwards never claimed he was innocent of the accusations leveled against him, however. In a 2003 interview with CBS News, conducted from a federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas, Edwards instead said that he never felt what he did justified a 10-year sentence.

“And most people in Louisiana feel the same way,” Edwards said. The proof, he said, was the more than 100,000 signatures gathered on a petition seeking his early release.

“To my critics out there, I want them to know that they’re getting what they wanted: I’m suffering. But to my friends, I want them to know I can handle it,” he said in the 2003 interview.

In a 2017 WWL-TV interview, Edwards also made a point to say that none of the charges against him stemmed from during his time in office.

“The conviction that I got, unfair or fair, whatever you want to call it, had nothing to do with my being governor. Nothing,” he said.

While in prison, Edwards filed for divorce from his second wife Candy. The two had been married for 10 years.

When he was released from prison in 2011, it was almost as though he’d never left the public eye. He celebrated his wedding to Trina Scott and his 84th birthday with a party at the Hotel Monteleone. Guests paid $250 each to watch friends roast the former governor.

Back in the public eye, at least occasionally, Edwards appeared at book signings and made personal appearances. Many times, he said, people urged him to run for office again.

His federal conviction meant he couldn’t run for governor but did not bar him from waging a campaign for Congress. In 2014, he ran in the 6th Congressional District which includes the Baton Rouge area, as well as Houma and Thibodaux. Edwards made the runoff but lost to Republican Garret Graves.

During a 2013 appearance at LSU, Edwards was asked by interviewer Larry King to ponder the reality that the first line of his obituary, no matter how much good he may have done for the state, includes the fact that he was convicted and served time in prison.

“Probably so, and that's par for the course,” Edwards said. “But I will say that all the elections I ran in over the years, in all but one I was at the top of the ballot, so I must have done something right.”

Funeral arrangements are pending, according to the family, but will include lying in state in the rotunda at the Louisiana State Capitol for visitation by the public.

- With reporting by Danny Monteverde and Clancy DuBos